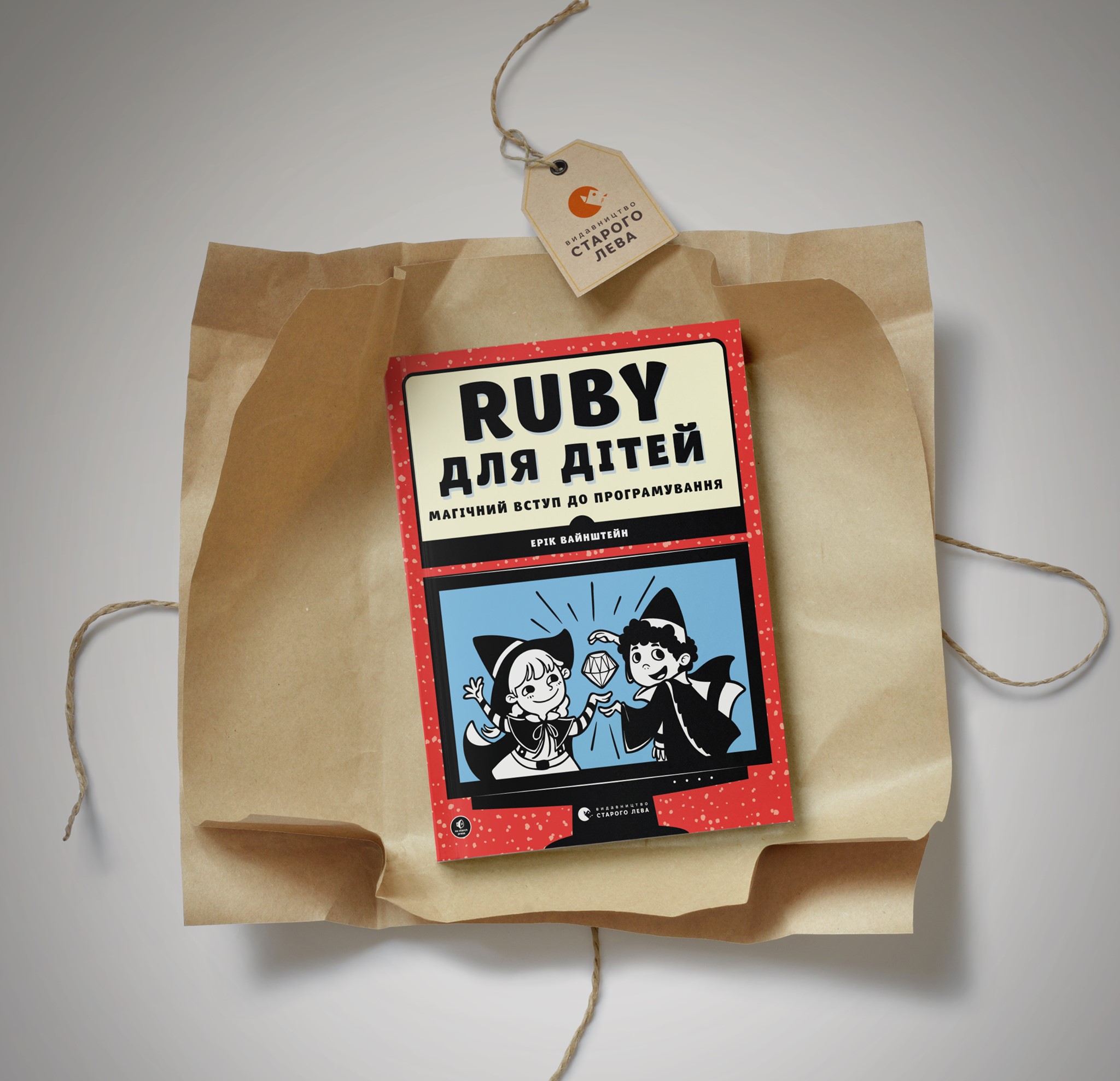

Ruby Wizardry translation to Ukrainian

The Ruby Wizardry book translation into Ukrainian is published!

I got involved with this book quite unexpectedly: a friend of mine who is a core member of local Ruby community #pivorak decided to translate this book into Ukrainian. As she was working through the book, we discussed and brainstormed a lot about how to best express many different puns, made-up words, exclamations in Ukrainian, how to translate character names and preserve their flair, how to pick the right name for various contraptions which might not be familiar to Ukrainian kids. All of this turned out to be very difficult; some sentences we worked on for days. Irina enlisted the help of the Ruby community as well, for example to come up with Ukrainian replacements to a plethora of humorous and witty exclamations the characters used.

An interesting challenge was about preserving or changing the genders of some characters to make the story sound more natural in Ukrainian language. There is an outstanding explanation about this difficulty on stackexchange, which I’d copy here:

Russian has a long standing tradition of narrating fables (stories featuring anthropomorphic animals).

In this tradition, the grammatical gender of name of the species (not necessarily the proper name of the animal) should be the same as the biological sex of the animal.

Some have mentioned Jungle Book’s Bagheera (who had been made a female in Russian adaptation), but this has little to do with his name.

The translator did not see any problem with Akela or Rama or other characters with declension I names, as long as she could put a masculine species name on them: волк, буйвол etc. Raksha is a female wolf, волчица, so she gets to stay a female as well.

However, this is a issue with пантера. The translator was faced with a problem: pick another species (she could have used леопард), make the readers accept that пантера is a boy in this story, or change Bagheera’s gender.

I don’t know why didn’t the translator choose the option 1, but the option 2 (leaving everything as is) was so bad that going through the pain of changing Bagheera’s sex through the story and having to cope with arousing difficulties was a better option.

Different authors choose different strategies for dealing with that, but in most cases, either the species or the sex gets changed, and only in rare cases the species name gender and the biological gender are left different:

- When translating “The Ant and the Grasshopper”, Krylov picked another species instead of grasshopper, a dragonfly (стрекоза), apparently to give the fable a better rhythm. Of course she was made a female. He left the word попрыгунья (“a jumper”) though, even though dragonflies don’t jump.

- In “Winnie-the-Pooh” adaptations, the Owl (Сова) was made a female character, though a Russian word филин does exist. In “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi”, Chuchundra (a rat, крыса) and Karait were made females. Even though the Russian word крайт exists and is masculine, it was deemed too unfamiliar to the Russian reader, so Karait was made just a snake, змея, and hence female.

- In “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, the Dormouse (Соня) is female. The Caterpillar in different translations is either female (Гусеница) or changes the species (Червяк, “The Worm”).

- As you mentioned, changing the species name from masculine to feminine is almost always an option in Russian, so I can’t think of a reverse situation off the top of my head (changing the biological sex from female to male in the story), but would not be surprised if it was ever the case.

So the answer to your question would be that:

You just don’t write a traditional story about a male zebra in Russian. That’s not how Russian story telling works.

The Russian word for zebra is feminine, so a zebra character should be female. If he should be male, he should not be a zebra.

The book can be ordered here: https://starylev.com.ua/ruby-dlya-ditey

I am very happy with the print quality of the book, it actually surpassed my expectations. Very pleasant to see and read!